(Pictured above: Minton majolica cheese dish)

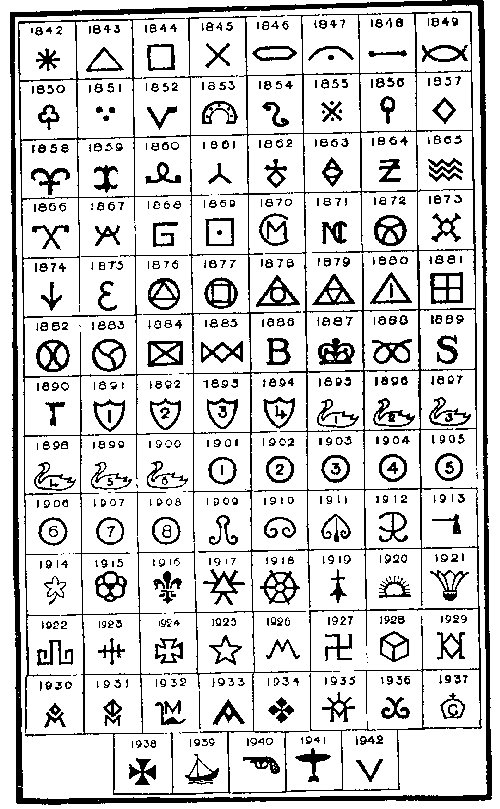

Minton were fortunately pretty good at marking their wares. There will invariably be an impressed mark on the Majolica pieces. The name Minton or Mintons (used after 1873) all appear. Little symbols were also used as the year cypher – thereby allowing the collector to easily pinpoint a year. You also will find a shape number: a number of publications today do print the marks. They list all the shape and pattern numbers.

Remarkably, many of the original factory design books survived which makes the task of identifying pieces, even if unmarked, a touch easier today. Most wares don’t carry artist’s signatures but the larger pieces may bear the signature or monogram especially if a well-known name such as Paul Comolera and John Henk was involved.

Maiolica

tin-glazed earthenware produced in Italy from the 13thC, although the term ‘maiolica’ was not coined until the 14thC. It originally applied to hispano-moresque lustreware imported to Italy from Spain via the island of Majorca – from which the word is thought to be derived. Maiolica production reached its peak during the 16thC at centres such as Faenza and Florence, and led directly to the development of faience in France.

Majolica

19thC British and US lead-glazed earthenware which echoed the strong colours, rich relief work and thick glazes of 16thC Italian maiolica, especially that produced by the della robbia family in Florence, Italy, in the 16thC. Majolica was introduced in Britain by Minton, using a cane-coloured body to set off the thick, coloured glazes. wedgwood followed suit, reviving its 18thC green-glazed ware with leaves moulded in relief, and using a white earthenware body and translucent glaze. The finest exponent of all, however, was probably George Jones, also of Staffordshire. The popularity of majolica spread to Sweden, throughout Europe and North America in the late 19thC, often drawing design ideas from the Far East.

The Majolica market has seen a few fakes and buyers should be cautious as always.

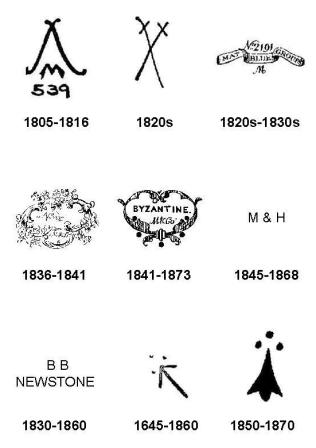

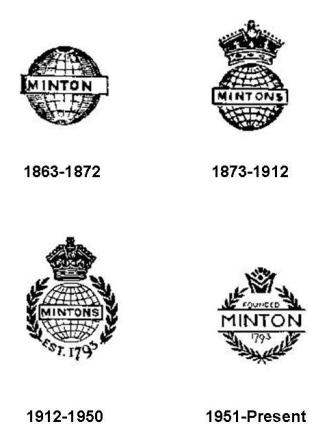

Minton: The factory founded by Thomas Minton in 1796. At first pottery only was made but soft-paste porcelain was produced probably as early as 1798. In 1817 Minton took his sons into the business and the firm traded as Thomas Minton & Sons. The father died in 1836 and John Boyle entered the firm which then became known as Minton & Boyle until 1845 brought a new partner, Michael Hollins, and a new style, Minton Hollins & Co. In 1883 the present style of Mintons Ltd was adopted.

Porcelain was not produced in any great quantity at Minton in its early years, but about 1825 several Derby artists took employment with the firm and output-and quality-increased. Sevres provided a recurring inspiration which extended to the marking of many pieces. Parian ware was a noted product from about 1845; and Marc-Louis Solon, who had been with S6vres, introduced the celebrated pate-sur pate technique. It is generally agreed that Minton made some of the best porcelain produced in England during the Victorian period-and indeed they still produce porcelain of fine quality.

Marks: include the letter ‘M’, the Sevres-like mark, the name ‘Minton’ impressed or transfer-printed.

Marks and Identification

Some Minton ware bears impressed marks which indicate the date of manufacture:

The Majolica Holy Grail?

Perhaps the most extraordinary marvel was the grand Majolica fountain by John Thomas. Known as the St George fountain, it stood over 30ft high, and over 40 ft in diameter and was made up of over 350 separate parts! It was produced for the 1862 exhibition. The skill and effort which would have had to have gone into producing a work of this scale is unimaginable by today’s standards. Almost as unimaginable was its disappearance in Bethnal Green in 1929. Priceless if ever found.