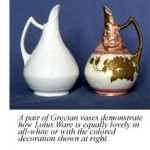

Lotus Ware is considered to be possibly the finest porcelain ever produced in the United States. It was made during the 1890s by East Liverpool’s own Knowles, Taylor & Knowles pottery.

Lotus proved to be so delicate that only about one in every twelve pieces made it through these kilns unscathed.

Knowles was an East Liverpool, Ohio potter whose pottery was a longtime producer of common Rockingham pottery, yellow Queensware, and ceramic canning jars. East Liverpool, nicknamed Crockery City, boasted dozens and dozens of potteries by the 1880s. The city produced nearly half of all American domestic, restaurant, and hotel china.

Knowles was an East Liverpool, Ohio potter whose pottery was a longtime producer of common Rockingham pottery, yellow Queensware, and ceramic canning jars. East Liverpool, nicknamed Crockery City, boasted dozens and dozens of potteries by the 1880s. The city produced nearly half of all American domestic, restaurant, and hotel china.

Around 1870, Knowles decided that it was time for a change. He brought into the company his sons, Homer and Willis, and his son-in-law, Colonel John Taylor. Certainly he wanted to involve family members in the business, but he was also canny enough to know that he was bringing in like-minded progressives. Knowles had already earned a handful of patents having to do with pottery industry machinery and energy consumption. He knew that his sons and John Taylor were as forward-thinking as he, and would keep the pottery headed in the right direction: straight ahead into the 20th century.

Knowles was right. Shortly after their arrival, the Knowles brothers and John Taylor added white ware, or ironstone, to the product line in 1872. This proved so successful a venture that within a year, Knowles, Taylor & Knowles (or KT&K, as it was by then known) had completely abandoned production of the less-refined Rockingham and yellow ware. It was now 1880, and KT&K, with five kilns, was the largest pottery in East Liverpool.

KT&K’s modern practices didn’t stop with the production of ironstone. They equipped at least one of their ironstone kilns with a heat source of natural gas, claiming to be the first pottery in the world to do so. Beyond this, the company established an in-house shop instead of farming out design and decoration work as many potteries did.

It was in tackling bone china that Isaac Knowles planned to make his mark.

The company wanted to create something rare and beautiful: art that simply happened to be rendered in porcelain. The extraordinary result was Lotus Ware. It may be no coincidence that Lotus Ware appeared on the scene in 1892, right around the time that First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison had decided that no domestic ceramics were fine enough for the White House.

The company wanted to create something rare and beautiful: art that simply happened to be rendered in porcelain. The extraordinary result was Lotus Ware. It may be no coincidence that Lotus Ware appeared on the scene in 1892, right around the time that First Lady Caroline Scott Harrison had decided that no domestic ceramics were fine enough for the White House.

Lotus Ware was essentially the brainchild of two men. The first, an English pottery technician named Joshua Poole, was well-versed in clay chemistry and arrived in East Liverpool fresh from the Belleek pottery in western Ireland.

The other man mainly responsible for Lotus was a pottery designer/decorator–or “fancy worker,” in the pottery lingo of the time–named Heinrich Schmidt. Schmidt, a German had worked previously at the famed Meissen factory, was undoubtedly a rare talent, but he was temperamental as well. He spoke no English when he arrived in East Liverpool.

Today, only about 5,000 pieces of Lotus Ware survive. The most comprehensive collection on display is at East Liverpool’s Museum of Ceramics, a tiny gem of a showcase for local pottery from the 18th century through today. There are a number of substantive private collections in the East Liverpool area as well.

A century later, though still not widely known outside East Liverpool, Lotus Ware continues to command attention among discerning collectors of American porcelain.

Despite some pieces having brought tens of thousands of dollars at auction, those willing to watch and wait have been known to find Lotus pieces for a few hundred dollars. Less, if they are willing to turn a blind eye to hairline cracks or mended handles.

Among porcelain devotees and ceramics scholars, the lustrous glaze that distinguishes every piece of Lotus is still considered peerless. In fact, the term “Lotus” comes from the translucent pearliness of that glaze, which Isaac Knowles had once observed resembled the glowing sheen of a lotus blossom. Beyond the glaze, there is much to admire in Lotus Ware: its singular delicacy, the lush and fantastical ornamentation, and perhaps most of all, the stubborn Americanness of its very existence.

Lotus Ware Marks