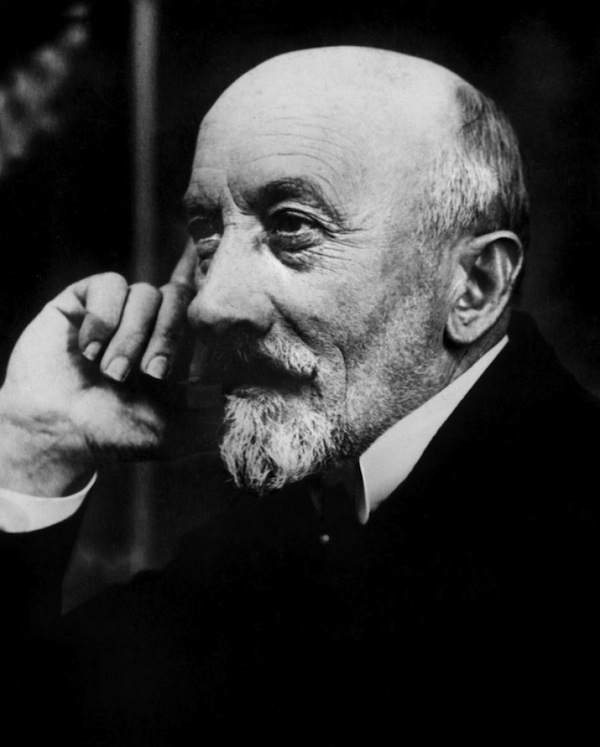

The shift in consciousness away from films as animated photographs to films as stories, or narratives, began to take place around the turn of the century and is most evident in the work of the French filmmaker Georges Méliès.

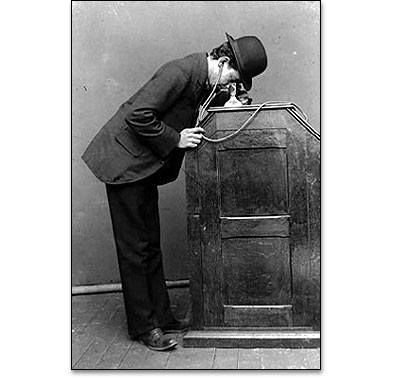

Méliès was a professional magician who had become interested in the illusionist possibilities of the cinema. The Lumières refused to sell him a camera he bought an Animatograph projector from them in 1896 and reversed its mechanical principles to design his own camera.

The following year he organized the Star Film company and constructed a small glass-enclosed studio on the grounds of his house at Montreuil, where he produced, directed, photographed, and acted in more than 500 films between 1896 and 1913.

Initially, Méliès used stop-motion photography. This is where the camera and action are stopped while something is added to or removed from the scene. Filming and action are then continued to make one-shot “trick” films in which objects disappeared and reappeared, or transformed themselves into other objects entirely.

These films were widely imitated by producers in England and the United States. Soon, however, Méliès began to experiment with brief multi-scene films, such as L’Affaire Dreyfus (The Dreyfus Affair; his first, 1899), which followed the logic of linear temporality to establish causal sequences and tell simple stories.

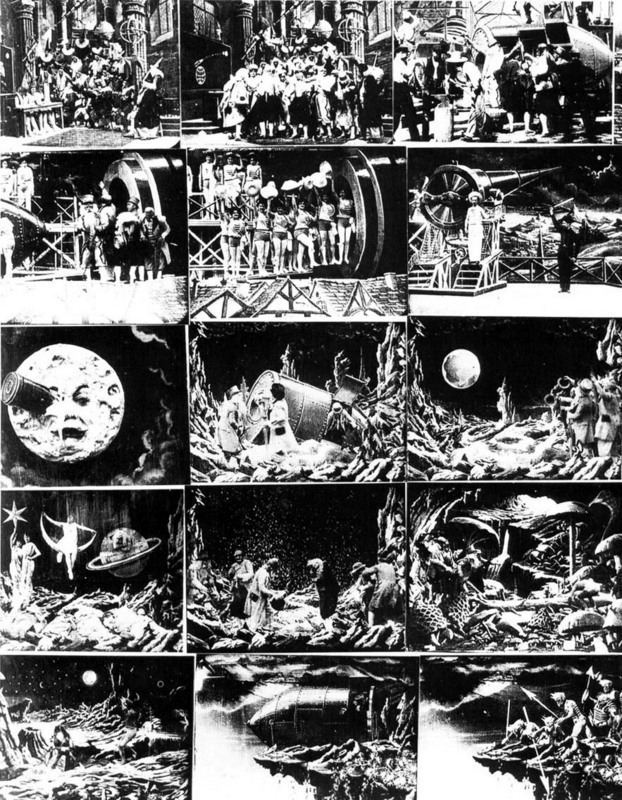

By 1902 he had produced the influential 30-scene narrative Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon). Adapted from a novel by Jules Verne, it was nearly one reel in length (about 825 feet, or 14 minutes). The first film to achieve international distribution (mainly through piracy), Le Voyage dans la lune was an enormous popular success.

It helped to make Star Film one of the world’s largest producers (an American branch was opened in 1903) and to establish the fiction film as the cinema’s mainstream product. In both respects Méliès dethroned the Lumières’ cinema of actuality.

It helped to make Star Film one of the world’s largest producers (an American branch was opened in 1903) and to establish the fiction film as the cinema’s mainstream product. In both respects Méliès dethroned the Lumières’ cinema of actuality.

Despite his innovations,Méliès’ productions remained essentially filmed stage plays. He conceived them quite literally as successions of living pictures or, as he termed them, “artificially arranged scenes.” From his earliest trick films through his last successful fantasy, La Conquete du pole (The Conquest of the Pole, 1912), Méliès treated the frame of the film as the proscenium arch of a theatre stage, never once moving his camera or changing its position within a scene.

He ultimately lost his audience in the late 1910s to filmmakers with more sophisticated narrative techniques.