Sculpture of the Inuit is descended from the ancient craft of carving, honed for generations on the land. Most objects traditionally made were useful in very specific ways. A nomadic people could take little else with them besides the tools of their daily living. A few small objects were carved. Such things as delicate earrings, dance masks, amulets, fetish figures, intricate combs and labrets are precious museum pieces today. In recent decades, Inuit have turned these skills to producing larger works whose austere beauty has astonished the art world.

Prehistoric Arctic Art

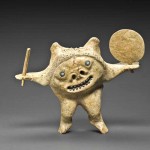

The first people known to produce a significant amount of figurative art were the Dorset culture (c. 600 BC-1000 AD). They carved bone, ivory and wood into birds, bears, other land and sea animals, human figures, masks and face clusters. It is believed that these works were worn as amulets or used in shamanic rituals.

Around 1000 AD, the people of the Thule culture migrated from northern Alaska and replaced the Dorset culture. Their art included some human and animal figures, but consisted primarily of the graphic embellishment of utilitarian objects such as combs, needle cases, harpoon toggles and gaming pieces. The decorative and figurative incised markings on these objects do not seem to have had religious significance.

Inuit Sculpture in Recent Times

The Thule culture ended in the 16th century, about the same time as contact with the white man began. Inuit began to barter with whalers, missionaries and other foreigners. Carvings of animals, as well as replicas of tools and western-style objects most often fashioned from ivory, became common trade goods.

Commercial carving began when the Canadian federal government recognized its potential economic benefit to the Inuit and actively encouraged the development and promotion of Inuit sculpture. In 1949, in Montreal, the Canadian Handicraft Guild introduced Inuit carvings to the world. By the 1960s, co-operatives had been set up in most settlements and the Inuit art market began to flourish.

Raw Materials

A variety of raw materials are used when carving. Some carvers also combine the different media of stone, whalebone, antler, ivory and muskox horn. Preference for one medium over another often depends on the availability of the raw material to the carvers of the community.

Stone

The term soapstone has been used to describe the raw material for carving in the Northwest Territories. Actually there are few soapstone deposits in the NWT. Soapstone is made of talc steatite and is very soft. Serpentinite, the usual stone used, is a different class of mineral, much harder, does not scratch with your thumbnail and comes in a variety of colours. Other stone found in the Arctic and used in carvings are silstone, argillite, dolomite, quartz and marble.

Adequate supplies of accessible, good quality stone form the starting point for carvings. For example, a deposit found at Aberdeen Bay in 1954 has been the source of millions of dollars worth of Lake Harbour and Cape Dorset carvings. The Mary River-Nuluujaak Mountain area deposit found in July 1981 supplies Pond Inlet, Clyde River, Igloolik and Hall Beach.

Most Inuit carvings are made from light to dark green or black serpentine-rich rocks that are correctly named serpentinite. The purest and best material has a distinctive yellowish-green colour, is very hard and takes a good to excellent polish. Some pieces may contain veinlets of white serpentine asbestos and others tiny black magnetite crystals.

The second most common carvingstone is argillite. The distinctive carvings from Arctic Bay and Sanikiluaq are made from argillite which ranges from light green to almost black, often has a distinctive striped grain and takes a beautiful polish.

Stone is often in short supply and artists must travel great distances over land or by boat to quarry good quality stone using hammers, chisels, shims and wedges and crowbars. Sometimes gasoline-powered drills and a non-explosive demolition agent (S-mite) are used. Local Inuit share carvingstone without question among their communities.

Whalebone

Weathered bone is found at sites once occupied by the ancient Thule people, who followed the great bowhead whales along the coast into the central and eastern Arctic. They used whale ribs as roof spars on their half-buried sod houses. Nowadays, Inuit carvers find a different inspiration in the curving shapes and pitted textures of the bone.

Ivory

Ivory in the Arctic is obtained from the canines of walruses and whale teeth of both the sperm and killer varieties. As a unique and identifying feature, polished surfaces of ivory show a pattern of light and dark diamond-shaped areas like an elongated checkerboard.

Incising carved objects with thin lines, a traditional practice that extends back into Arctic prehistory, gave rise to scrimshaw, the ornamentation of shells, ivory and bone by engraving. The peak years of scrimshaw art coincided with the zenith of the whaling industry, in the 1830s to 1850s. Complex scenes were “drawn” on ivory with fine, sharp tools. Filling the incised lines with lampblack, soot, charcoal or India ink brought out the detail. Tobacco juice was sometimes used to give a sepia effect. The completed, inked engraving was polished with whale oil and china clay, pumice powder or sailmaker’s wax and canvas.

Horn

Muskox horn carvings have a soft, rippled texture, shading from cream to warm brown. The shape of the horn itself is not usually recognizable as artists freely use their imagination to evoke the animal and human subjects the material suggests to them.

Evolution of an Inuit Stone Carving

The carver chooses the stone and looks at the hidden creation in its shape. He begins by sawing the stone into a block. With the introduction of more modern tools, electric saws are also used. The rough image is then hacked out by hand tools.

Using a large file, defining details are delineated. Caribou antler is often affixed to the handle of the file for comfort. A smaller file is used for the finer details. Electrical tools, such as flexible shafts, are also used. To smooth the carving, the carver uses a strip of sandpaper which he pulls under his thumb giving both control and consistency to the movement and quality of sanding.

The carving is then put into water, ready for further sanding with wet and dry sandpaper, commencing with a rough grade to a very fine grade. The carver can tell by feel when the carving is ready for polishing. This final stage varies with carvers, some preferring a high polish, others preferring to leave the carving in unpolished form.

Imagery and Styles

The Inuit population of about 25,000 is widely distributed across Canada’s north and each of the art-producing communities has developed its own favourite subjects and sculptural style.

From the islands, we see representations of Arctic wildlife, particularly birds and marine mammals. Generally naturalistic in style, they can be somewhat stylized, sharp-edged and angular in appearance, incised with minute detail.

From the eastern Arctic come a variety of styles. Some are rooted in a love of naturalism and an interest in both wildlife and the spirit world, often fashioned into almost impossibly thin shapes or delicately balanced works. Some incorporate a love of the flamboyant, the dramatic and the decorative. The stone ranges from many beautiful shades of green to white dolomite and varicoloured marble. Green stone, especially the apple-green and cream-coloured shades are particularly highly prized.

Yet other sculptures exhibit a certain heroic realism in animal and human subjects, working on a large scale in portrayals of dramatic and emotionally charged shamanic or mythological images. From one community the sense of humour and whimsy results in images such as dancing walruses of bone. Sculptures have soft, undulating outlines and are highly finished. Some whalebone and stone sculptures are large and rather fantastic in conception, combining the surreal and the whimsical. Yet others depict the drama of the hunt.

Some communities are best known for their ivory miniatures which were encouraged by local missionaries. Animals or genre scenes, with an unpretentious folk art flavour, are the most common subjects.

From the central Arctic, Keewatin steatite stone is grey to black in colour and very hard. The large, heavy and dynamic carvings of hunters and animals have little surface detail but hold considerable emotional power. The muskox is a favourite subject. Female carvers produce depictions of mothers and children. Scenes of animal-human transformations are also common.

Also seen are small composite depictions of traditional camp life fashioned from various types of stone and incorporate wood, copper, whalebone and antler. Often featuring igloos with detachable tops, they are descriptive and somewhat static in nature. Recently, muskox horn has become a popular carving material. Its sweeping curves are readily transformed into elegant long-necked geese.

No two pieces of Inuit sculpture are ever alike. The techniques and styles are as varied as the backgrounds of the artists themselves: Men and women, old and young — they live across the Arctic, influenced at times by their peers in the communities. Their works are found in galleries throughout the world and are a fine investment. Pieces bought a few years ago have sometimes appreciated many times over.