Scotland’s national drink has grown from clandestine distilling in the 17th century to become one of the country’s major industries and leading exports known the world over.

The exact origins of Scotch whisky are unclear, many aspects of the golden beverage are certain if not surprising.

Could the Irish take the credit for first making Scotch whisky? It is true that the Scots (or Scotti) – some of the original settlers from Ireland – brought their Gaelic language and culture when emigrating to Scotland beginning in the fifth century. Many landed on Islay, the island that became the administrative centre for early kings. It coud be that commerce was active there and alcohol production was one of the by-products of the island’s early success.

No historian (at least none from Scotland) will claim the Irish were responsible for what is now the country’s national drink.

The popularity of both single malt and blended whisky has soared in recent years. The drink is sold in more than 200 countries; France and the US are among the leading purchasers and imports are surging in China.

The ingredients of Scotch malt whisky are barley malt, water and yeast. Barley is second to oats as the nation’s top-producing crop and is primarily grown in the north-east, or Speyside, the heart of whisky country. Grain whisky is a mixture of the above ingredients along with unmalted wheat and maize. Burnt peat (dead plants) adds a phenolic – or smokey – depth to the final product.

What do we know for certain about Scotland’s whisky heritage? It wasn’t until 1494 that there was a record of the brew being produced here. The Scottish Exchequer Rolls that year notes the provision of “eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aquavitae”. The Malt Whisky Society equates eight bolls to 1,120lbs or 508kg — enough malt to make 400 bottles of today’s whisky.

Friar John and other monks were among the first to make the concoction produced for both personal enjoyment and medicinal reasons. While wine and beer production took place in abbeys and monasteries across England, the distillation of grains only occurred in Scotland. Scots wanted a beverage of their own.

Chemists have never been able to discover precisely what determines the special character of the product of each distillery or exactly why it is that maturing affects such an improvement in flavour.

The increase in whisky production was soon followed by the government’s desire to benefit financially. The first tax on spirits was imposed by the Scottish Parliament in 1644.

After the Union between England and Scotland, London imposed the malt tax in Scotland at half the English rate. The unpopular move ensured there would be a black market for whisky and helped to explain why many of today’s distilleries are in the north and west of Scotland – areas often too far for the tax man to seek out.

The Scots, even the Church, banded together to hide their whisky-making handiwork. This included placing small stills in caves and bottled goods in houses of worship. The illicit spirit is said to have even been shipped by coffin.

George Smith, of Glenlivet fame, was the first Speyside distiller to become a legitimate, tax-paying whisky maker. The decision was quite unpopular among the locals and prompted Smith to carry a firearm for protection.

Historians generally point to two key events that helped raise the profile of whisky. In 1831, Aeneas Coffey invented the patent still, which allowed for a continuous distillation process.

About 50 years later an insect devastated French vineyards, causing panic in the country’s wine and brandy markets. The Scots took advantage by offering a hearty spirit that was free of the plant-eating beetles.

The passing of the Spirit Act of 1860 brought about even greater production. The Usher family of Edinburgh produced grain whisky – which added about 85 per cent unmalted maize or wheat to the remaining 15 per cent barley malt – to develop the first blended whiskies for a broader audience. Therefore, blended whisky is a mixture of malt and grain whiskies. The lighter flavoured grain spirit was used to reduce the intensive flavours of the malt whiskies.

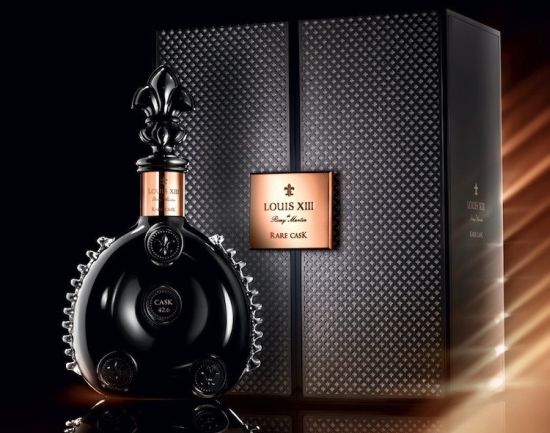

Some whisky offers a distinct appearance because it is aged in oak casks. The barrels, used once to make Spanish sherry then shipped to Scotland, help give maturing whisky a mellowing effect and darker colour. New barrels produce straw-coloured whiskies, while some distillers by law are permitted to add caramel to produce a consistent shade.

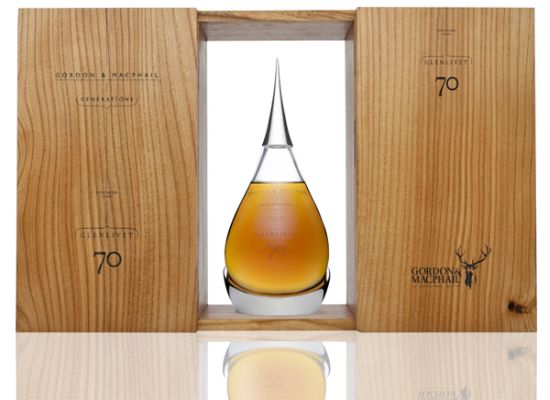

Why do only some whisky labels include the age of the product? The minimum age of whisky is three years. If a distillery mixes a batch that is three years old with one that has matured for 20, the age of the full production is three. That’s the law, and that’s why some makers don’t publicise the age. The general belief is that 15 years is peak maturation time for Scotch whisky, although older whisky is just as tasty.

Whether 15 or 115, you are likely to know something about the great Scots poet Robert Burns. While living in Ayrshire, Burns, a socialist, was an excise man chasing down illicit whisky stills for the government? As much as he enjoyed sipping a wee dram, “Rabbie” was also a keen and accurate taxman who took his job seriously.

Burns knew intimately what he was writing when he penned the poem John Barleycorn.

And they hae taen his very heart’s blood,

And drank it round and round;

And still the more and more they drank,

Their joy did more abound.

John Barleycorn was a hero bold,

Of noble enterprise;

For if you do but taste his blood,

‘Twill make your courage rise.

The poem is a teasingly accurate description of the whisky-making process. He paints a vivid picture of the production and of a drink that has an enormous uplifting effect on the soul.

Burns, the national bard, loved his country and its drink. And his most popular work, Auld Lang Syne, is synonymous with Scotland the world over.

Raise a glass to Burns, Scotland and whisky!

Eight bolls (63.5 kilos) is a substantial amount of whisky and, according to the NAS, is evidence that whisky was being produced in Scotland well before 1494.

It is possible, therefore, that an earlier reference to Scotch whisky could still be discovered.