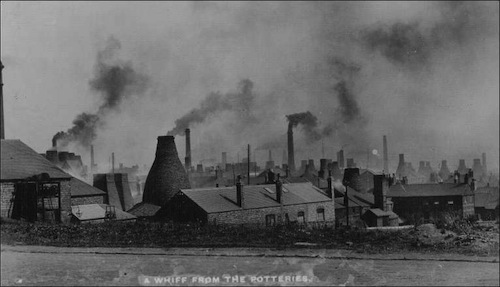

From the 18th century until the 1960s, bottle ovens were the dominating feature of the Staffordshire Potteries. There were over two thousand of them standing at any one time and they could be seen everywhere one looked.

Some small factories had only one bottle oven, other large potbanks had as many as twenty-five.

Within a factory ovens were not situated according to any set plan. They might be grouped around a cobbled yard or placed in a row. Sometimes they were built into the workshops with the upper part of the chimney protruding through the roof.

No two bottle ovens were exactly alike. They were all built according to the whim of the builder or of the potbank owner.

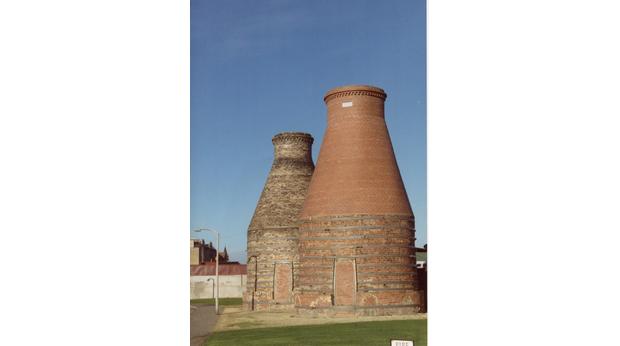

These pottery kilns are the last remaining buildings of the pottery industry in Scotland. As such, they are a vital part of Scottish industrial heritage and deserve to be recognised world wide. Situated in Portobello, Edinburgh, they are the only reminder of our community’s industrial history and we are determined to ensure their future care and maintenance. Portobello Heritage Trust has been formed with their initial project being to secure the future of the kilns. We are working in partnership with the City of Edinburgh Council to take this forward. Membership is open to individuals, groups and companies world wide and we welcome support from our own and the wider community.

These kilns fired objects created by the potters in Buchan’s Pottery, which was located in Portobello for over one hundred years before relocating in 1972. Originally utilitarian objects such as ginger beer bottles, whisky flagons and hot water bottles were produced before innovative ideas led to the creation of decorative tableware of various patterns and colours, some of outstanding quality. These objects are much sought after today and provide an insight into the skills of these craft workers.

Some of the smaller factories had only one bottle kiln but the larger factories or as they were called potbanks had as many as twenty-five. Within a factory the kilns were not situated according to any set plan.

They might be grouped around a cobble stone yard or placed in a row. Sometimes they were built into the workshops with the upper part of the chimney shooting up through the roof.

No two bottle kilns were exactly alike. They were all built according to the whim of the builder or of the potbank owner. There are an amazing number of bottle kilns on the skyline still today between

Burslem and Longport England.

The weird bottle shaped brick buildings looked like they had been borrowed from a fairytale scene. Experts figured that in the hay day there were up to four thousand bottle kilns with as many as two thousand still standing in the 1950’s. The Clean Air Act sounded the death knell for this smoky, coal fired kiln.

Construction of the kiln

The outer part, which is bottle shaped is known as the HOVEL. A HOVEL can be up to seventy feet tall. The HOVEL acts as a chimney; taking away the smoke, creating draught and protecting the kiln inside from the weather and uneven draughts.

A doorway, the CLAMMINS or WICKET, surrounded by a stout iron frame and just large enough for a man with a SAGGAR on his head to pass through, is built into the kiln.

A SAGGAR is a fireclay container, usually oval or round, used to protect pottery from marking by flames and smoke during firing in a bottle kiln.

Placing pottery in saggars required special knowledge.

Plates were reared or dottled, which means that they were carefully separated from each other by thimbles to prevent the glaze from making them fuse together in the glost firing. The finished saggar was fired in the kiln and lasted for thirty to forty firings if they were not broken

SAGGAR MAKER A skilled man, producing the finished saggar.

BOTTOM KNOCKER A young apprentice potter that made the base of the saggar from a lump of fireclay which he knocked into a metal ring using a wooden mallet or mall.

Young boys, known as bottom knockers, in 1921 with two malls, the tool used for bottom knocking.

FRAME FILLER A male apprentice that flattened a mass of clay and produced a rectangle which was wrapped round a drum to make the side of the saggar. Around the base of the oven are

FIREMOUTHS The exact number depends on the size of the kiln, in which fires are lit for the firing. Inside the kiln directly above each FIREMOUTH is a

BAG This is a small firebrick chimney, the purpose of which is to direct the flames from the fires below into the kiln and protect the SAGGARS nearby. Underneath the floor of the kiln are the

FLUES Which lead from each FIREMOUTH, and distribute heat throughout the interior. In the center of the kiln floor is the

WELL HOLE over which SAGGARS, with their bottoms knocked out, are placed. This forms a chimney to allow the smoke to escape. This is called the

PIPE BUNG Placing the pottery in the kiln

The SAGGARS were arranged in vertical stacks called BUNGS which extended from the floor of the kiln to the ceiling. When they were full, the SAGGARS were carried into the kiln by PLACERS, who balanced them on their shoulders and heads. The weight of a full SAGGAR was approximately fifty pounds. To protect their heads and to keep the SAGGARS in place, the PLACERS wore rolls made from old stockings which were wedged into the front of each man’s cap.

The pottery was arranged differently in the SAGGARS, according to whether it was BISCUITWARE, which all pottery is called after its first firing or GLOSTWARE, which is pottery that is in the process of being glazed.

Firing Different Types Of Pottery In A1 Bottle Kiln

BISCUITWARE

For HOLLOWARE, which is cups bowls, jugs and vases, the bottom of each SAGGAR was covered with a thin layer of powdered flint or silica sand, and as many pieces as possible were then packed in.

FLATWARE, which is dishes, plates and saucers was bedded which means a layer of pottery was placed on top of a layer of silica sand or powdered flint and was covered with another layer of sand and flint.

On top of this was placed yet another layer of ware which in its turn was covered with a layer of sand or flint.

This continued until the SAGGAR had been filled with alternate layers of sand or flint and ware.

The purpose of this method was to reduce warping.

GLOSTWARE

During this firing, it was necessary to separate all the pieces so that when the glaze melted, they would not fuse together. To separate the pottery in the SAGGARS, different kinds of kiln furniture were used. This included PINS, SADDLES, THIMBLES and SPURS. Inside the oven, the SAGGARS were stacked from floor to ceiling, in BUNGS.

Starting at the rear of the oven, the BUNGS were SET-IN from the walls towards the center. The PLACERS gradually worked their way around the ovens towards the CLAMMINS (door) and in the last section the BUNGS were set from the center towards the door until the oven was full. Because the floor of the oven was sloping, the heavy BUNGS had to be wedged with pieces of broken SAGGAR, to enable them to stand upright.

Because the temperatures within the oven varied widely, it was necessary to place the different types of pottery in carefully selected locations. This warranted some terribly skilled workers, because if the smoke got in it, it could damage all the pottery inside. Sulphur and all sorts of stuff out of the coal could do quite a bit of damage.

Firing The Bottle Kiln

On average, the bottle kilns were fired once a week. A BISCUIT, which is the first firing, took three days and a GLOST which is the second firing, took two days. It required about fifteen tons of coal to fire one bottle kiln once, because almost half the heat generated would go up the bottle shaped chimney as smoke.

The smoke, emerging some sixty feet up, would move in a circular motion contrary to the direction of the main smoke column and curl down onto the buildings and street, even entering workshops and houses through ill fitting windows and half open doors, so that the air became terribly polluted. In Longton the town with the greatest number of bottle kilns, it used to be said, “It’s a fine day if you can see the other side of the road”, and when the bottle kilns were firing it was almost impossible to see your hand held in front of your face.

After placing the CLAMMINS, the entrance to the kiln was blocked up with bricks and sand and the kiln was then ready to fire.

Fires were lit in the FIREMOUTHS and BATTED, that is, coal was loaded onto the fires at intervals of about four hours. In the early stages of firing the temperature was kept low while the moisture in the ware was driven out.

This was known as SMOKING.

After about 48 hours, the maximum temperature between 1832 F and 2282 F was achieved and this was maintained for approximately two to three hours. The fires were then left to go out. Fine control of the draught was achieved by altering the position of the DAMPERS in the CROWN.

DAMPERS are flaps made from iron and firebrick, which the fireman could operate from ground level by means of a pulley system. By opening selected DAMPERS, the draught in different sections of the kiln could be increased, thus causing the fires to burn more fiercely and raising the temperature. By closing the DAMPERS the temperature could be kept steady or lowered.

When the firing was over, the CLAMMINS was broken down and the kiln left to cool. As soon as it was sufficiently cool for a man to enter without being harmed by the heat, the kiln was emptied or drawn. There is evidence that men often had to enter kilns which were too hot, because the factory owner required the pottery urgently.

In such cases, to protect themselves to some extent, the men wore wet rags over their hands and faces. When you would let your fire go out on your kilns, you were supposed to wait forty eight hours until it would cool.

Some kilns used to be opened after twenty four hours and it would still be red hot inside. Then men would climb on inside and they used to have five overcoats on and about three jackets wrapped around their wrists, and they would have to lift the saggars down with his padded arms.

THE FOUR MAIN TYPES OF BOTTLE KILNS

The Updraft Kiln

This is the basic type of kiln. It consists of an inner chamber with a domed roof in which the pottery was placed enclosed within a HOVEL. FLUES and BAGS lead from the FIREMOUTHS to the center of the kiln, and conducted heat to the potterys inside. The heat rose up through the contents of the kiln (the SETTING) and out through the top. This type of kiln was used for firing both BISCUIT and GLOST pottery firing.

The Downdraft Kiln

This type of kiln which used heat more efficiently than the UPDRAFT kiln was developed in the early 20th century. It is similar in shape to the UPDRAFT kiln, but the draft was controlled in such a way that the heat first rose and then was forced downwards again through the SETTING and out through holes in the base of the kiln.

The hot smoke was then sucked up through a straight chimney nearby which served one or more neighboring kilns. This type of kiln is used for both BISCUIT and GLOST pottery firing.

The Muffle or Enamel Kiln

A MUFFLE kiln is very much smaller than the other types of kilns and is used to fire decorated pottery.

Decorated pottery was fired in order to make their colors permanent because without firing, they could be washed or rubbed off. A MUFFLE kiln does not require a temperature as high as that used for BISCUIT or GLOST pottery firing. The flames do not enter the firing chamber, instead the kiln is heated by means of encircling flues. In this way the delicate colors are protected.

The Calcining Kiln

There is no particular reason a CALCINING KILN should be bottle shaped, since it is used not to fire pottery, but to prepare the flint and animal bones which are added to clay to make up the material from which pottery is made. This material is called the BODY. Before the flint or animal bones can be added to the BODY, they have to be crushed to a fine powder. If they are burnt or CALCINED, they become brittle and can be powdered with ease.

Remaining Kilns

Burslem

3 Downdraught bottle kilns at Acme Marls Ltd, Bournes Bank.

2 Very tall conical kilns in Furlong Lane.

1 Experimental muffle kiln in Moorland Pottery, Moorland Road.

1 Kiln at Moorcroft Works, Sandbach Road, Cobridge.

1 Large bottle kiln at Price & Kensington Works, Newcastle St, Longport.

1 Square calcining kiln at Millvale Street, Middleport.

2 Calcining kilns, 1 round, 1 square, Newport Road, Middleport.

1 Bottle kiln at Burgess & Leigh, Port Street, Middleport.

Hanley

2 Updraught kilns at Johnson Brothers Pottery, Eastwood Road.

1 Large kiln at Dudson. Hanover/Hope Street.

1 Bottle kiln with enclosing buildings, Lichfield Street.

1 Updraught kiln at former J H Weatherby works, Old Town Road

1 Kiln and buildings at former Smithfield Pottery, Warner Street/Potteries Way.

2 Kilns at the old Twyford Works, Shelton New Road, Shelton.

Stoke

1 Bottle Kiln with hexagonal base, rising to oval top, former Dolby Pottery, Lytton Street.

2 Updraught kilns and buildings at Falcon Works, Sturgess Street.

Fenton

1 Kiln and three story building, Chilton Street, Heron Cross.

3 Calcining Kilns, Fountain Street.

Longton

4 Kilns at Enson Works, Chelson Street.

2 Bottle Kilns within a workshop range, Commerce Street.

2 Kilns at Albion Works, King Street.

1 Bottle Kiln, corner of Warren St / Normacot Road.

2 Kilns at Sutherland Works, Normacot Road.

1 Tall Kiln at rear of Sutherland Works, Normacot Road.

1 Slender circular hovel to calcining kiln, Uttoxeter Road.

7 Kilns at Roslyn Works (now Gladstone Museum), Uttoxeter Road.

TOTAL OF BOTTLE KILNS LEFT: 47

All of the forty seven remaining kilns are on a historical registry

NEW LIFE FOR OLD KILNS

Work began in May 2001 in England to restore 12 bottle kilns which had fallen into disrepair. Four of the sites were restored, protected and made available for public viewing using lottery funding and other money from Staffordshire Environmental Fund and the site owners. The funding was granted nearly four years earlier, but the complexity of site investigations, negotiation with site owners and preparatory work meant that it took that long before any of the restoration could be started. After hitting that snag, the Potteries Preservation Trust, which was created in order to commission the restoration, applied for listed building consents to fit most of the bottle kilns with a glass cap and to do repair and alteration work.

The glass cap prevented rain from getting into the kilns but would allow air to circulate so they could not be further damaged from dampness. The brick work was repaired and repointed while rusty ironwork holding some of the structures together was also replaced.

Four kilns at the Enson Works in Normacot Road, Longton, were included in the grant but were restored at a later date because they formed part of a much larger restoration of a factory. The bottle kilns are important to protect because they give the potteries its historical identity. Some bottle kilns have already been restored to good condition such as those at the Gladstone Museum, but others are still in very poor condition.

Although they are all listed, the co-operation of the site owners is needed to restore them and they were hoping once the work was done people would see the benefits and they could tackle some of the others.”

Although they lie inside factory premises, all the kilns to be restored will have to provide public access at least up to the entrance.

Mike Jones, managing director of James Kent Ceramic Materials, said his firm’s bottle kilns had been used until the late 1980s for calcining flint for use in tableware. He said: “We were concerned about the upkeep of the kilns and we are now very pleased they will be preserved.” A one time there were more than four thousand bottle kilns in North Staffordshire but most of them were demolished after the 1950s Clean Air Acts and that is why only 47 remain.