In the 19th century, educated ladies and gentlemen sat at their desks writing letters and making entries in their diaries. Of course, this opened up a market for manufacturers to produce desk accessories including paperweights. Made by master craftsmen, they are objects of supreme beauty. Is it any wonder that they were hardly ever used for such a mundane task as securing loose papers?

Although paperweights had been produced in Venice, probably as early as the 15th century, the major period of production was between 1845 and 1860 by the great French glass making factories of Baccarat, Clichy and St Louis. During this period and later, they were made in other countries like the UK, the USA and Bohemia but these generally did not match the superb quality of the three French factories.

There are several different kinds of paperweights. Perhaps the best- known is millefiori, literally a thousand flowers. This is a technique perfected by Venetians glassmakers although probably it was used first in ancient Greece and Rome.

Glassmakers take a number of relatively short, thin, coloured glass canes. These are put together, perhaps in a group of twelve, then heated till they fuse together, still retaining their individual colours. The new, thicker cane is then pulled with pontil rods attached to both ends until it is about thirty times its original length and the diameter has shrunk from perhaps six inches to quarter of an inch. Then it is cooled and cut into very small pieces.

The tiny pieces of fused glass are assembled inside a metal ring. They stand on their ends, so displaying the different colours of original the rods giving the impression of small flowers. They are arranged in a pattern and molten glass is put on top. The millefiori stick to it and more molten glass is added until it is the required size. Before the glass cools it is fashioned into shape and then allowed to cool slowly.

There are a number of traditional patterns using millefiori. For example, in a torsade, loops of coloured, ribbon-like glass encircle the centre design. Then there is carpet millefiori where the patterns are so close together they look like a carpet. In garland paperweights, millefiori are arranged in circles or hoops, giving the impression of garlands of flowers.

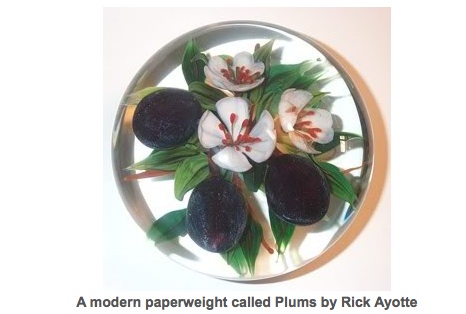

Lampwork, a technique perfected by Venetian craftsmen in the 16th and 17th centuries, is another traditional method of making paperweights.

Small pieces of coloured glass are heated using a blowlamp until they are molten. They are shaped into flowers, animals or other design and then encased in glass to produce the finished object. The designs in a paperweight produced by lampwork can be amazingly realistic and can give the impression that a real flower or butterfly, for example, have been used instead of ones made from glass.

Another technique for making paperweights involves using sulphides, sometimes called cameo encrustations.

During the 18th and 19th centuries ancient classical objects came into fashion. Of course, there weren’t enough ancient Greek and Roman artifacts to satisfy demand so reproductions were made in a variety of materials. This led to cameos and other decorative porcelain plaques being made into paperweights. Encasing porcelain in glass was a revolutionary technique bringing with it a number of problems, the main one was finding a ceramic material that could withstand the heat of molten glass.

French craftsman, Pierre Honoré Boudon de Saint-Amans and British glassmaker, Apsley Pellat, separately perfected the technique in the early 19th century. In 1819 Pellat patented Crystalo Ceramie, a kind of porcelain with a higher melting point than glass.

The technique that both Apsley Pellat and Pierre Honoré Boudon de Saint-Amans used was to make a sulphide plaque, fire it and allow it to cool. It was then gradually reheated while a bubble of glass was blown. When the bubble was the right size, a slit was made in it, the plaque inserted and the hole pinched together to seal it. The glassblower then sucked the air out of the bubble so collapsing it onto the sulphide plaque.

There is another technique used for encasing sulphides; glass is placed above and below the plaque rather than the sulphide going inside a glass bubble.

Beware of paperweights with poorly modelled flowers or other designs. They are a sign of inferior workmanship.