The 7th to the 9th century was the heyday of the “illuminated manuscript”. Production of these works took place in the monasteries scattered across Europe. These religious retreats were the repositories of those texts of Greece and Rome which survived in Europe. They were also the seats of the intellectual life of Europe during the Middle Ages.

Monks in the monasteries made copies of the books in their care, both religious and secular manuscripts. However, they did not contribute much more to the advancement of that intellectual tradition because they were not engaged in thinking about the relationship between the works in their care and the world outside the monastery.

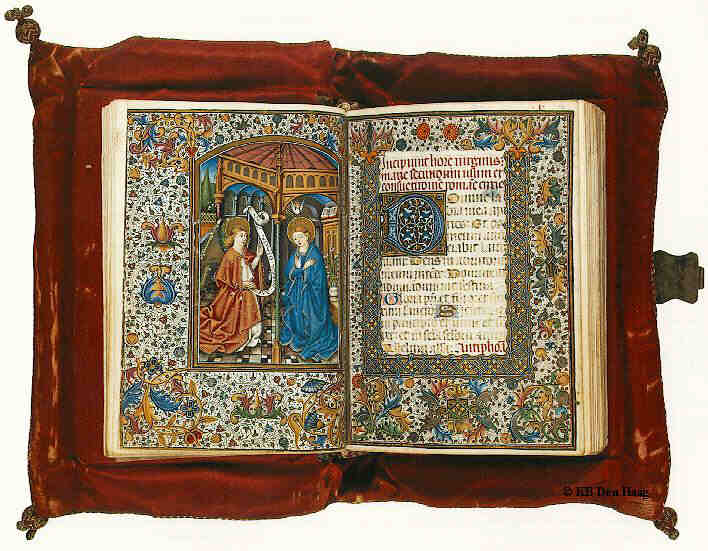

During this time, the production of Bibles was the place where the arts of the monastic scribes and later lay artists, bloomed. It was here that the most elaborate and beautiful illumination found its outlet and the manuscript books from this period represent the height of the art of decoration.

The most important thing about the manuscript books of this period is that they were objects of religious veneration. They were seen as consecrated objects. Their creation was an act of religious devotion. The monks who sat for years, working on single chapters of the Bible, were not reproducing books. They were making the word of God manifest in the world.

The style of these books is very different from anything we are used to reading. They are not meant to be a collection of words that convey information from an author to the reader. Their primary function is to serve as decoration which pays tribute to the word of God.

In an illuminated manuscript, the complexity of the decoration was intended to mirror the complexity of the biblical passages illustrated. Just as Biblical text is open to many different interpretations, the illumination of that text was intended to be the same.

However, interlacing and interweaving of the bodies of snakes and lions, of peacock and fishes, chalices and vines, is not intended to be a naturalistic representation of the existing world. The images are schematic and symbolic. The elements of the work are chosen from a repertoire of marks and usable images and themes, a set collection of pre-agreed symbols, forms, and images.

The images are meant to represent some aspect of Christ’s life. The snake representing rebirth (in the shedding of its skin) and also Original Sin. The peacock representing the incorruptibility of Christ (a reflection of the ancient belief that the flesh of a peacock is incorruptible).

Modern books appear as illustrated, but the illustration and photographs, the images, are usually distinct from the text. In these early manuscripts dedicated to God, the two were not so separate.

The decoration is carried into the text. There is a continuity between the words and the decoration which suggests that the illuminated religious manuscript, is an attempt to convey the beauty of God’s message to mankind.

For all their beauty the manuscripts of the monasteries did little to affect life in Europe. Primarily this comes about as a consequence of the inaccessibility of the monastic libraries.

Instead of books being openly available as they are today, manuscript books were mostly locked up in monasteries strewn across Europe. Given the amount of time and energy and financial resources which went into their production, books were far too valuable to make available to the general public.

There was no way to use them for scholarship, even the few secular texts that may have been available.

This problem was compounded by the lack of a uniform cataloguing system in the monasteries. Therefore even with access to the library of a monastery, there was no way of knowing what was in the collection, or where it might be located.