Art nouveau could be said to be the first 20th century modern style. It was the first style to stop looking backwards in history for ideas, taking inspiration instead from what it saw around it, in particular the natural world.

When art nouveau was showcased first in Paris and then in London, there was outrage; people either loved it or loathed it. Within the style itself there are two distinct looks: curvy lines and the more austere, linear look of artists such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Some aspects of art nouveau were revived again in the 1960s.

Style

- sinuous, elongated, curvy lines

- the whiplash line

- vertical lines and height

- stylised flowers, leaves, roots, buds and seedpods

- the female form – in a pre-Raphaelite pose with long, flowing hair

- exotic woods, marquetry, iridescent glass, silver and semi-precious stones

Influences

- arts and crafts – art nouveau shared the same belief in quality goods and fine craftsmanship but was happy with mass production

- rococo style

- botanical research

Well known names

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh – architect and designer of furniture and jewellery

- Alphonse Mucha – posters

- Aubrey Beardsley – book illustrations

- Louis Comfort Tiffany – lighting

- René Lalique – glass and jewellery

- Emile Galle – ceramics, glass and furniture

- Victor Horta – architect was an American-born artist noted for his avant garde graphic design and poster art, especially in Britain.

Introduction to art nouveau and art deco

Art nouveau and art deco are two of the most significant movements to emerge in the last years of the 19th and the early 20th century. The appearance of furniture and applied arts of this period was dramatically altered by these new styles.

‘Art nouveau’ derives its name from a shop in Paris, La Maison de l’Art Nouveau, which retailed glass and furniture designed by such innovatory figures as René Lalique, Emile Gallé and Louis C Tiffany. Most art nouveau objects are characterised either by sinuous fluid forms derived from nature, or, particularly in Britain, by simple straight-lined designs with a heavy vertical emphasis.

‘Art deco’, named after the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, embraces two very different approaches to the applied arts. On the one hand, designers made luxurious objects of the highest quality. On the other, modernists developed clean, simple shapes suitable for mass production.

Almost any type of object reflecting these styles is highly collectable

In the middle years of the 20th century, art nouveau and art deco became rather unfashionable, but today almost any type of object reflecting these styles is highly collectable, although prices for many small, mass-produced objects are still relatively low.

Ceramics

Pottery of this period provides something to suit almost every taste and it can make an ideal subject for inexperienced collectors. Most pottery and porcelain is marked, wares by the most famous potters are usually well documented and many pieces are still refreshingly inexpensive.

Styles

Plates and vases of the art nouveau era are covered with floral and organic shapes or languid, scantily clad maidens in the style of the movement. In stark contrast, the clean, bright motifs and avant-garde shapes of art deco pottery from the 1920s and 1930s evoke the spirit of their age.

William Moorcroft

If you see a piece of pottery decorated with raised lines which look as if they’ve been applied with an icing nozzle, the chances are it was made by William Moorcroft at the famous Macintyre Pottery in Staffordshire. This Iris vase illustrates the distinctive technique, known as tube-line, which was made with hand-applied fine lines of slip (liquid clay). It would fetch about £700.

Royal Copenhagen

The serpentine movement of this group and its soft pastel shades identify this as a typical piece of Royal Copenhagen porcelain. The group, known as “The Rock and the Wave”, is so popular it’s still produced today. An item like this would cost between about £700 and £900.

Dating can be tricky for a piece that’s been produced over several decades, but different marks were used and these can give a clue as to the date of manufacture. These are some Royal Copenhagen marks.

Doulton & Co

This factory produced such a wide variety of wares that many buyers collect nothing else. You’ll have to pay more if a piece was made by a famous designer. The vase at the top of the page was decorated by the prominent designer Mark V Marshall, and would be worth over £5,000. A piece by a less prestigious designer might be worth a tenth of the price.

Clarice Cliff

The most famous British art deco potter, Clarice Cliff, produced such a huge number of different shapes and designs that whole sales are now devoted entirely to her wares. Value is largely determined by the rarity of the design. Small objects or anything in the Crocus pattern are usually the most affordable.

Look out for:

- Condition. This will affect the value enormously and restoration can be difficult to spot. Check spouts and handles for signs of chipping and run a finger around rims and bases to see if they’re intact.

- Shape. Futuristic shapes, like this unusual teapot (shown above) with its distinctive curving lid, are a keynote of Clarice Cliff’s adventurous pottery. A piece like this, which dates from around 1935, would cost about £300 to £500.

- Colour. The warm, yellow-honey glaze gives the background an ivory colour seen on many Clarice Cliff wares.

- Outline. Decoration is often outlined in black.

- Brush strokes. Although produced in large quantities, all genuine Clarice Cliff was hand painted and you should be able to see brush strokes in the coloured enamels.

Spotting a fake

The many Clarice Cliff reproductions and fakes can usually be distinguished by their inferior colour and design. This jug looks washed out compared with the vibrant colours in the teapot, and the handle is too thin.

Desirable designs

- Age of Jazz figures

- Wall masks

- Inspiration series

- Circus series, designed by Dame Laura Knight

- Graham Sutherland designs

- Frank Brangwyn circular plaques

Furniture

Whether you want to become a serious collector of art nouveau or art deco or pick up a few pieces to furnish your home in period style, you’ll find original furniture in a wide range of quality and prices. The most sought-after and valuable pieces are large, commissioned, handmade items by known designers. Smaller objects and original mass-produced furniture are widely available and relatively affordable.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh

One of the most influential British Art Nouveau designers, Charles Rennie Mackintosh usually designed his furniture to commission. The clean simple lines of the chair above are in stark contrast to the fluid forms of most French art nouveau furniture. This chair would cost £15,000.

Liberty & Co

Furniture made for the influential firm of Liberty & Co is usually marked with a Liberty label and, though highly collectable, is affordable. This dressing table is part of a set which also includes two wardrobes. The suite would be worth £1,500.

Emile Gallé

This small table is designed by Emile Gallé , one of the leading French exponents of the art nouveau style, and is worth between £7,000 and £10,000.

It has five features characteristic of most Gallé furniture:

- strong sculptural quality

- inventive design

- fruitwood marquetry inlay

- stylised floral decorative motifs

- a signature

Pieces marked Gallé which lack the originality of earlier designs and are less inventive in their use of inlay may have been made by Gallé’s firm after his death. Although collectable, they’re not as valuable as pieces made in Gallé’s lifetime.

Barcelona chair

Originals of this Barcelona chair were first made by designer Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1929 and have been mass-produced continuously since World War II. Chairs that predate mass production are worth around £10,000 – ten times more than later versions. They can be recognised by:

- a bent chrome top rail with separate sections joined by lap joints and screwed with chrome-headed bolts

- a welded stainless steel top rail

Affordable art deco

Much unsigned furniture of the 1920s and 1930s remains relatively inexpensive. A typical item such as this cocktail cabinet would be worth £800 upwards.

Quality can vary. You should look for:

- uncracked veneers

- original upholstery

- pale woods

- dramatic but simple geometric forms

Glass

Distinctive and highly decorative, art nouveau and art deco glassware includes a wealth of opportunities for the collector. Designers of the era found creative ways to use glass, making vases, lamps and objects as diverse as car mascots, and jewellery.

Designers

Unlike most earlier glass, the value of art nouveau or art deco glass is dependent largely on its maker or designer. This was the heyday of influential glass makers such as Emile Gallé, Daum and Lalique in France, and Louis Comfort Tiffany in America.

All named glass is widely collected, and the best pieces are very expensive, but you can still find unmarked pieces or smaller objects for relatively modest prices.

Gallé glass

The best pieces, such as this lamp, are made from hand-carved cameo glass, formed by fusing two or more layers of coloured glass with the top layer carved to reveal the colours underneath. Later machine-made versions are less valuable and are identifiable because the carving is not so deeply cut. An item like this would be worth £15,000 or more.

Gallé pieces are usually marked with a cameo or incised-carved signature. If you see a star after the signature, the piece was made during the first three years after Gallé’s death, between 1904 and 1907.

Daum Frères

Glass made by the Daum brothers is often very similar to that made by Gallé but can usually be identified by a gilt signature, “Daum Nancy”, on black enamel on the underside. This vase would cost about £2,000.

Tiffany

Tiffany lamps have bronze or gilt bronze bases. The shades are made from a lattice of bronze set with small pieces of favrile (iridescent) glass, marked with an applied bronze pad. A lamp like this would be worth at least £10,000.

Lalique

All types of glass made by the most famous glass designer of the art deco period, René Lalique, are highly collectable. His prolific output included car mascots, clocks, lighting, jewellery, furniture and figurines.

Lalique pieces are extremely valuable. The Bouchon Mûres scent bottle with tiara stopper shown at the top of the page is worth about £15,000. But Lalique’s distinctive wares were also much imitated, so be alert for lookalikes.

How to identify a Lalique

The genuine article is characterised by:

- Inventive design. If not, it could be by Marius E Sabino, whose work is often reminiscent of Lalique’s but less elegantly proportioned. This opalescent vase by Sabino would fetch about £500.

- Heavy weight. Modern fakes are usually lighter in weight than authentic pieces.

- Authentic colour. With coloured glass, modern fakes such as this red vase are sometimes in colours never used by Lalique. The red Lalique-style vase is worth about £400, while the real Lalique, the blue glass Sauterelle vase, should fetch £5,000.

- Fine detail. If it’s opalescent glass, the effect should be more noticeable on high-relief areas and less noticeable on thin walls. Other makers also produced opalescent glass, including Sabino and Etling. This opalescent figurine is by Edmund Etling & Cie and is worth about £1,000.

- The maker’s mark. The real thing should be marked ‘R Lalique’ , possibly with ‘France’ and a model number. Sabino pieces are usually marked with a moulded engraved signature.

Fakes

Fake art nouveau glass abounds. Among the objects most likely to deceive are:

- Tiffany lamps with fake marks. These are identifiable because they do not usually have the marked pad on the shade.

- Cameo glass marked Gallé. A fake is recognisable by its stiff, lifeless decoration.

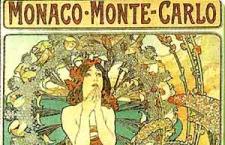

Posters

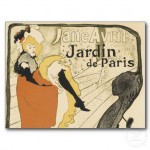

The era of art nouveau and art deco saw artists such as Alphonse Mucha and Adolphe JM Cassandre use their skills to design advertising posters. The designer, aesthetic appeal and condition of a poster all influence its value.

Alphonse Mucha

Mucha’s posters usually combine a romanticised female figure with elaborate details such as flowers, plants and drapery. An original poster like the one above is worth around £3,000.

Printing techniques

The growth of the art nouveau movement coincided with the development of increasingly versatile printing techniques, enabling artists to produce a wide variety of poster designs. The main types are:

- Engraving. Copperplate is incised with the design, then inked and used to make prints.

- Etching. Copperplate is coated with wax into which the design is scratched. The plate is then inked as before.

- Lithograph. The design is drawn on stone. Then the different colour areas are treated with an ink-resistant chemical and the stone is inked and used for printing.

- Photogravure. The image is photographed and the negative is applied to a plate which is then etched or engraved.

Art deco posters

Art deco posters are usually strikingly simple and focus on a single dominant image, with strong emphasis on lettering. This poster for the liner Normandie is the most valuable of the posters designed by the famous French artist Cassandre and is worth around £6,000.

Condition

Many posters were printed on cheap paper and have suffered from foxing (brown spots), tearing, fading or staining. Avoid those that are badly damaged or glued to a back board. This Jules Chéret poster is in unusually good condition and thus it could be worth as much as £900.

Is it old?

Art nouveau and art deco posters have been the subject of a great many reproductions in recent years. It shouldn’t be too hard to tell the difference.

- Reproductions are on modern paper – it’s thicker than old paper and usually glossy.

- Modern colour printing techniques use tiny dots you can see with a magnifying glass. Authentic lithographs have flat areas of colour.

Sculpture

Art nouveau and art deco figures were popular in the early 20th century. Art nouveau sculptures tend to show women in dreamy poses or draped around functional objects, while the art deco women of the jazz age are playing golf, dancing or smoking.

Ferdinand Preiss

The most valuable art deco sculptures are usually those made from a combination of bronze and ivory called chryselephantine. The figure above dates from the 1930s and was made by Ferdinand Preiss, one of the most famous sculptors of such figures. A piece like this would be worth about £4,000.

Is it bronze?

Many less valuable art deco figures were made from a bronze spelter (zinc alloy) base combined with ivorine, a simulated ivory usually made from plastic. To identify spelter scratch the metal underneath. A yellow colour means it’s made from bronze, while a silver tone shows it’s spelter and far less valuable.

Gustav Gurschner

This bronze nautilus shell lamp by the Bavarian sculptor Gustav Gurschner is a typical mix of form, function and decoration. Made in about 1900, it’s worth in the region of £3,000. Similar fluid shapes were favoured by French sculptors. English pieces are usually less stylised.

Sculpture care

The patination of a bronze – the surface sheen it acquires through ageing – is fundamental to its appeal. Never polish a bronze or you will seriously reduce its value.

Demètre Chiparus

The bases of art deco sculptures are integral to the composition and can provide a clue to the identity of the maker. The architectural quality of the base of this figure is typical of DH Chiparus. A piece like this would fetch about £9,000.

Art Nouveau in the City

![]()

Despite its emphasis on nature, Art Nouveau was predominantly an urban style, created to decorate the streets and interiors of modern industrial cities, which had expanded rapidly during the last third of the nineteenth century. The cities represented in the exhibition demonstrate the international variations of Art Nouveau. Although each city developed its own version of the style, all shared similar ideas and goals.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Art Nouveau swept through the cities of Europe and North America, embodying the novelty and complexity of the modern age. The style was short lived, however, and by the outbreak of the First World War, it had disappeared. While some aspects of Art Nouveau, such as its flowery curvilinear designs, went rapidly out of fashion, others influenced later art and design movements. The application of the highest aesthetic standards to the everyday things of life was further developed in the 1920s by German Bauhaus designers, who also emphasized the importance of design in creating a “total work of art.” In addition, the rectilinear style favored by many Art Nouveau artists prefigured the geometric simplicity and abstracting tendencies of much twentieth-century art and design.

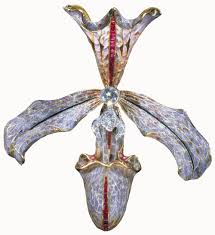

Hair ornament in the form of an orchid, made by Philippe Wolfers, Belgium, 1905-7. Museum no. M.11-1962

Philippe Wolfers was the most prestigious of the Art Nouveau jewellers working in Brussels. Like his Parisian contemporary René Lalique, he was greatly influenced by the natural world. These exotic orchids feature in the work of both. The technical achievement of enamelling in plique-a-jour (backless) enamel on these undulating surfaces is impressive. Orchids symbolised the Art Nouveau movement and its fascination with nature, sensuality and exotic flowers.

Art Nouveau in Brussels

Brussels was also at the center of the development of Art Nouveau: many of its earliest and most important creations were either made or exhibited in the city. At this time Brussels enjoyed a new prosperity from the wealth it had gained during the Industrial Revolution and Belgium’s colonial expansion in Africa. The city underwent great change, and Art Nouveau became the style most representative of the transformation. In 1893 Victor Horta, the leading architect-designer in Brussels, designed Tassel House, the first fully developed example of architecture in the Art Nouveau style. Other influential Belgian designers included Henry van de Velde and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy. Both created furniture that blends an emphasis on structure with lyrical curvilinear elements abstracted from nature.

Art Nouveau in Chicago

After the Chicago fire of 1871, architects and structural engineers flocked there. As they rebuilt the city’s streets and structures, they developed a new form of architecture that was appropriate for the modern age. Among the principal architects working in Chicago was Louis Sullivan, one of the few American architects to find a place in the international Art Nouveau movement. His skyscrapers constructed around steel frames reflect the technological advancements of the age. Their exteriors were decorated with intricate ornaments inspired by forms in nature and by Celtic art. With these designs, Sullivan brought elements of nature into the urban landscape. His chief designer, George Grant Elmslie, created similar ornaments, such as the teller wicket for the National Farmers’ Bank at Owatonna. The designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, a disciple of Louis Sullivan, were also informed by the natural world, but Wright developed a very different aesthetic. Rigid and rectilinear, his buildings, furniture, and stained glass were much influenced by the art and architecture of Japan. The dining room furniture that he created for the Frederick C. Robie House in 1907 reflects his fascination with Japanese design.

Art Nouveau in Glasgow

Although Art Nouveau was not generally embraced in England, the style developed in exciting new directions in the Scottish city of Glasgow. Elements of vigorous industrialism, modernity, and ethnic pride all played their part in the particular strain of Art Nouveau that emerged there. The work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and other artists and designers of the Glasgow school is typified by a linear restraint. Inspired by Japanese art, they introduced into their designs a strict rectilinear geometry, along with stylized plant and figurative forms. Among Mackintosh’s most important patrons was Miss Cranston, a Glasgow tearoom owner for whom he designed several interiors. The Ladies’ Luncheon Room at Ingram Street typically integrated architecture, furniture design, and decorative glasswork.

Art Nouveau in Munich

Jugendstil was the name given to Art Nouveau in Germany. The term came from the title of the Munich periodical Die Jugend (The Youth), established in 1896. In Munich, as elsewhere, Art Nouveau was a complex style that found expression in a number of different approaches. Otto Eckmann, one of the leading and most prolific artists of the new generation, designed all manner of objects, from textiles and furniture to ceramics and metalware, which reflect the importance attributed to the applied arts at that time. His tapestry Five Swans became an icon of the Munich Jugendstil: its celebration and abstraction of natural forms, along with its sinuous lines and manipulations of space, define its modernity. In 1898 leading Munich designers Richard Riemerschmid and Hermann Obrist formed the Vereinigte Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk (United Workshops for Art in Handicraft), which promoted the production of modern design. Riemerschmid’s work illustrates the new priorities of Munich artists, reflecting both their obsession with nature and insistence on rational, efficient design.

Art Nouveau in New York

In the Art Nouveau period, New York became one of the world’s great economic and cultural centers. The patronage of an outstanding generation of industrialists and financiers led to the creation of public museums, libraries, and grand private mansions. In this environment of confidence and wealth, American artists and designers developed their own version of the new art. The most prominent of these was Louis Comfort Tiffany, one of the greatest glass artists and manufacturers of his time. He pioneered a wide range of visually distinctive, highly advanced glass technologies, creating key masterpieces in the Art Nouveau style. His sources of inspiration ranged from excavated Roman glass and medieval stained glass, to exotic Japanese, Chinese, and Islamic forms. Equally important was his scrutiny of plants and insects, which he transformed into colorful and sensual celebrations of the natural world. Included in the inaugural exhibition of Bing’s Paris gallery L’Art Nouveau, Tiffany’s creations were much admired by European artists and patrons.

Art Nouveau in Paris

Paris was the most important artistic center in Europe at this time, and many key developments in the formation of Art Nouveau took place there. From the mid-1890s, works by emerging young designers were exhibited at Bing’s gallery L’Art Nouveau. And the city hosted the World’s Fair of 1900, which also helped to bring Art Nouveau to center stage. At this time Hector Guimard, perhaps the most prominent Parisian Art Nouveau designer, was commissioned to design entrances for the city’s new subway system. With their organic and tense linear style and use of cast iron for both structural and decorative purposes, they are among the most famous icons of the Art Nouveau style. Artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, also associated with Art Nouveau circles, was particularly active in the graphic arts. His posters for café-concerts such as the Divan Japonais reveal the influence of Japanese art in their strong outlines and bold, flat patterns.

Art Nouveau in Turin

In Italy, Art Nouveau was known as stile floreale, a name derived from the curving, floral designs favored by the artists and designers there, or stile Liberty, after the famous store in London, which sold the work of modern designers. Turin was a leader in Italy’s economic growth at that time and an important center for the development of Italian Art Nouveau. In 1902, it hosted the Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna, the most ambitious display of international decorative art ever attempted. Leading Turinese furniture designers Vittorio Valabrega and Agostino Lauro both participated in the exhibition, as did the Milanese designer Carlo Bugatti. Lauro exhibited furniture from a room that he had designed for a villa belonging to a textile manufacturer in the Piedmontese town of Sordevolo. The room is a prime example of the Art Nouveau principle of Gesamtkunstwerk, combining architecture, furnishings, and decoration into a harmonious whole.

Art Nouveau in Vienna

Art Nouveau in Vienna was known as the Secession style after seminal Viennese artist Gustav Klimt led the city’s progressive artists and designers into forming the Vienna Secession group in 1897. Members of the group broke free from the conventions and constraints of existing Viennese art establishments by breaking down the barriers between art, design, and craft. Influenced by the geometry of the Glasgow school and the simplicity of Japanese design, the work of the Viennese designers is characterized by a restrained linearity and elegance. In 1903 Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, both members of the Secession group, established the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshops), which emphasized the important role of craftsmanship and an integrated approach to the design of interiors.

Art Nouveau Investment

What to invest in

Due to mass production, many art nouveau items are not valuable although still highly desirable. However, if the pieces is by a known designer, the price soars.

- Original Tiffany lamps – have a marked pad on the shade.

- Emile Galle glassware – usually have a cameo or signature.

- Posters – especially ones by Alphonse Mucha, Jules Cheret and J M Cassandre. To see whether they’re reproductions, feel the quality of the paper. Reproductions will be on thick, modern paper. Use a magnifying glass: if you can see tiny dots making up the colour it’s probably a reproduction. Genuine ones have flat areas of colour.

- Glassware by the Daum Freres – look for the marking Daum Nancy.

- Silverware – pill boxes etc, particularly anything marked Liberty & Co.

Where to see it

- The Hill House, Upper Colquhoun Street, Helensburgh, Nr Glasgow – designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh

- Glasgow School of Art – also by Mackintosh

- tiles in the food hall in Harrods

- Paris metro – some of the station entrances still have the signs designed by Hector Guimard

- Musée D’Orsay, Paris – has a large collection of art nouveau

- Criterion Brasserie, London

- Victoria and Albert Museum